WEBlog / paolotagliaferri.it

Nella terra dei lupi di Joe Wilkins

02/01/2021 - di Paolo Tagliaferri

Avevo pensato di acquistare questo bel libro su internet, così come ormai è prassi di molti, ancor più in questo sciagurato periodo in cui siamo flagellati da questa drammatica epidemia che ci induce inevitabilmente a limitare i contatti con il mondo che ci circonda. Ma poi mi sono diretto in centro ad Arezzo, in piazza Risorgimento, approfittando di uno dei pochi giorni classificati a rischio “giallo”. Fa sempre tutto un altro effetto acquistare un buon libro in questo piccolo negozio, “Il viaggiatore immaginario" che, rispetto alle altre librerie della città magari più grandi e fornite, è un luogo dove si respira la passione per le buone letture e non è semplicemente un luogo dove si vendono libri. Ero certo che lo avrei trovarlo e così è stato. “Nella terra dei lupi” (Neri Pozza editore) è il romanzo di debutto di Joe Wilkins, già autore pluripremiato per la raccolta di memorie della sua infanzia trascorsa in quelle zone remote del Montana e in cui è ambientata la storia di Wendell e Gillian e del piccolo Rowdy. Una terra di frontiera, tormentata e ostile, dove ancora oggi e forse in maniera ancor più marcata, la povertà rurale fa da sfondo a vite solitarie, a famiglie distrutte, in un circolo vizioso di violenza, degrado ambientale, alcol e mancanza di istruzione. Il ceto medio che non esiste più e che si abbandona inesorabilmente all’oblio. Poco meno di trecento pagine che vanno via in un paio di giorni e che, se la stanchezza del lavoro non mi facesse capitolare la sera dopo pochi capitoli, avrei potuto leggere tutte d'un fiato. Il mito della virilità del west americano fatto nuovamente a pezzi in questa storia tragica e struggente, come tante altre possono ambientarsi nella vastità della provincia rurale americana, un mondo che non sembra riuscire a trovare una via d’uscita alla propria miseria in quella che al momento permane, malgrado tutto, la più grande e ricca nazione del mondo. Terra arida e selvaggia, strappata con violenza oltre un secolo fa alle popolazioni native, ai Crow e ai Lakota che per secoli l’avevano abitata, rispettandola nella loro primitiva semplicità. L’avanzata dei coloni in cerca di nuove terre e la corsa all’oro ne avevano decretato, circa 150 anni fa, la resa definitiva. Tribù ormai decimate, affamate e stanche che proprio nella terra del Montana, nella valle del Little Big Horn, trovarono la loro ultima leggendaria vittoria sulle giubbe blu del Generale Custer. I discendenti di quei coloni sono il mondo in cui sopravvive il piccolo Rowdy di 7 anni, bambino un po’ ritardato, malnutrito e sbilenco, che viene affidato al cugino della madre. Una madre che non lo ha mai accudito a dovere, che lo lasciava sempre in casa da solo, distratta da una vita sconsiderata fatta di rapporti casuali, alcol e metanfetamine, fino ad essere imprigionata per spaccio di droga. Rowdy, che per giunta non parla più da mesi, viene accompagnato dall’assistenze sociale in una zona impervia del Montana, ai margine delle montagne, dove abita in una casa mobile l’unico parente che possa prendersene cura, il ventiquattrenne Wendell Newman. Il ragazzo non se la sente di mandarlo via, per quanto abbia già anche troppi problemi per tirare avanti, fra i pochi dollari che gli rimangono in tasca, un passato scomodo e un lavoro instabile. Ma con il passare del tempo Wendell riesce ad instaurare un legame prezioso con quel fragile bambino, nutrendolo, proteggendolo dal freddo, rimandandolo a scuola e restituendogli quel calore che nessuno gli aveva mai riservato. Fino al sorprendente epilogo che, nella sua innegabile tragicità, sembra accendere una lieve speranza di riscatto e redenzione, un deciso rifiuto alla violenza spiccia e insensata, unito al desiderio di proteggere senza tentennamenti le persone che si amano. Quell’ottusa violenza incarnata da uomini resi malvagi da una vita che li ha privati precocemente degli affetti familiari e di qualsiasi stabilità emotiva ed economica e che ne ha determinato i loro fallimenti e le loro tragedie, rendendoli poveri, sporchi e truci. Uomini che credono che solo con le armi potranno rivendicare la propria libertà e la propria supremazia sulle terre dei propri padri, contro un odiato Governo centrale che considerano l’unica causa delle proprie colpevoli disgrazie. Una terra che a loro giudizio non deve essere né protetta né salvaguardata, ma deve essere funzionale all’uomo e al proprio dominio e che giustifica la caccia di frodo indiscriminata, lo sterminio dei lupi delle montagne e le discariche fra i crepacci. Qualcuno ha definito questo romanzo una sorta di western moderno. Ma questa è solo una delle tante storia di uomini, di donne e di bambini che cercano unicamente di sopravvivere alle proprie disgrazie sullo sfondo di un mondo e di una terra ostile che sembra destinata ad un tragico destino. Personaggi che non riescono a trovare un senso alla propria esistenza, sopraffatti ed inerti e che neppure la fuga sembra poter salvare. Un romanzo che fa tornare alla mente le sconvolgenti notizie che giungono in questi giorni da un America già flagellata dalla spietata brutalità dell’epidemia di Covid-19 (oltre 350.000 morti), e che deve fare i conti con quello che passerà alla storia come l’anno con i maggiori morti in assoluto per overdose, oltre 81.000, dove eroina, metanfetamine e le nuove potentissime droghe sintetiche tipo il fentanyl, stanno sterminando soprattutto il ceto medio bianco e che dalle grandi città metropolitane sta invadendo la provincia americana e gli stati del west. Quelle morti, da molti catalogate semplicisticamente come “morti per disperazioni”, a cui si va a sommare un tasso di suicidi ormai fuori controllo (oltre 14 suicidi per 100.000 abitanti, circa 50.000 persone, quanto una popolosa città che scompare ogni anno), un dramma che sembra che nessuno vuole o riesca ad affrontare. Nelle aree rurali e meno popolose del paese, come nel Montana del romanzo di Wilkins, il tasso di suicidi e del 25% più alto che nelle zone con almeno un milione di persone. Numeri sconvolgenti, senza senso, e che sommandosi alle morti per abuso di alcol raggiungono valori inimmaginabili di oltre 160.000 persone che muoiono ogni anno “per disperazione” e il trend purtroppo è in continua ascesa. Il mito offuscato e forse inesorabilmente scomparso di una moderna società americana che non pare riuscire minimamente a trovare gli strumenti per mettere in pratica quelli che i propri padri fondatori avevano decretato essere, nella Dichiarazione d’Indipendenza del 1776, i diritti inalienabili per tutti gli uomini. Vita, libertà e felicità.

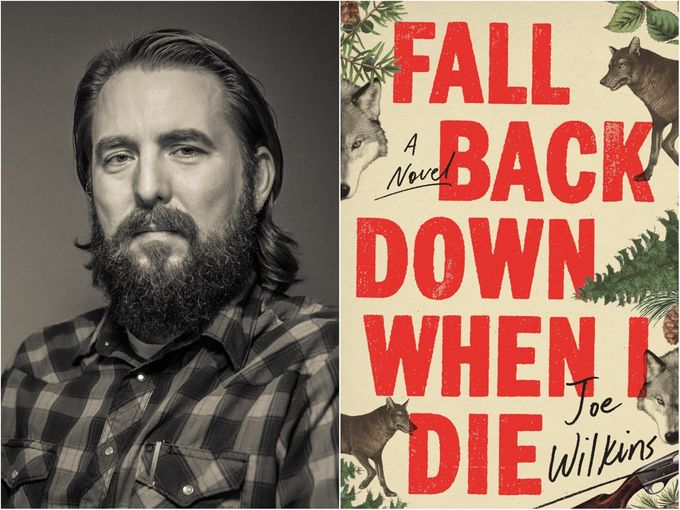

"Fall back down when I die” by Joe Wilkins

The misery of the American rural province

I had thought of buying this beautiful book on the internet, as many are used to do nowadays, especially in this unfortunate period during which we are plagued by such a dramatic epidemic, forcing us to limit the contacts with the world around us. But then I headed to the download of Arezzo, taking advantage of one of the few days whilst not in lockdown. It always makes a difference buying a good book in a small shop, which is a place, compared to other larger and more well-stocked bookshops in the city, where you can breathe the passion for good reading and not simply a place where books are sold. I was sure I would find it and I did. "Fall back down when I die" is the debut novel by Joe Wilkins, already an award-winning author for the collection of memories of his childhood spent in the remote areas of Montana, where the story of Wendell, Gillian and little Rowdy is set. A borderland, tormented and hostile, where even today and perhaps even more markedly, rural poverty is the backdrop to lonely lives and destroyed families, in a vicious circle of violence, environmental degradation, alcohol and lack of education. In such a context the middle class no longer exists and inexorably abandons itself to oblivion. A little less than three hundred pages that go away in a couple of days and which I could have read all in one breath, if the fatigue of the working day did not make me capitulate in the evening after a few chapters. The myth of the virility of the American West, torn apart again in this tragic and poignant story, like in so many others, can be set in the vastness of the American rural province, a world that does not seem to be able to find a way out of its own misery in a nation which remains, despite everything, the largest and richest nation in the world. An arid and wild land, violently stolen over a century ago to the native populations, the Crow and the Lakota, who had inhabited it for centuries, respecting it in their primitive simplicity. The advance of the settlers in search of new lands and the gold rush caused their definitive surrender about 150 years ago. Tribes now decimated, hungry and tired that right in the land of Montana, in the valley of the Little Big Horn, found their last legendary victory over General Custer's blue jackets. The descendants of those settlers are the world where little 7-year-old Rowdy survives, a slightly retarded, malnourished and lopsided child, who is entrusted to his mother's cousin. A mother who never looked after him properly, who always left him at home alone, distracted by a reckless life made up of casual intercourses, alcohol and methamphetamines, to the point of being imprisoned for drug dealing. Rowdy, who hasn't spoken for months, is accompanied by social assistance in an impervious area of Montana, at the edge of the mountains, where the only relative who can take care of him, 24-year-old Wendell Newman, lives in a mobile home. The boy doesn't feel like sending him away, although he already has too many problems to get by, with few dollars in his pocket, an uncomfortable past and an unstable job. But as time passes Wendell manages to establish a precious bond with that fragile child, feeding him, protecting him from the cold, sending him back to school and giving him back that warmth that no one had ever reserved to him. Until the surprising epilogue which, in its undeniable tragedy, seems to light a candle of hope for redemption: a decisive rejection of hasty and senseless violence, combined with the desire to protect without hesitation the people we love. That obtuse violence embodied by men made evil by a life that deprived them prematurely of family affections and any emotional and economic stability and that determined their failures and tragedies, making them poor, dirty and grim. Men who believe that only with weapons they will be able to claim their freedom and their supremacy over the lands of their fathers, against a hated central government that they consider the only cause of their own guilty misfortunes. A land that, in their opinion, must be neither protected nor safeguarded, but just functional to man and his domain, thus justifying indiscriminate poaching, the extermination of mountain wolves and landfills in the crevasses. Someone called this story a kind of modern western. But this is just one of the many stories of men, women and children who only try to survive their misfortunes against the backdrop of a hostile world and land that seem destined to a tragic fate. Characters who are unable to find meaning in their existence, overwhelmed and inert and whom not even escape seems to be able to save. A novel that brings to mind the shocking news coming in these days from the US, a country already plagued by the ruthless brutality of the Covid-19 epidemic (over 350,000 dead) and which has to deal with what will go down in history as the year with the greatest deaths from overdose ever, over 81,000. Heroin, methamphetamines and the new powerful synthetic drugs such as fentanyl are exterminating above all the white middle class and, moving from the large metropolitan cities, are invading the American province and the states of west. Those deaths, categorized by many simplistically as "deaths from despair", to whom you have to add a suicide rate currently out of control (over 14 suicides per 100,000 inhabitants, about 50,000 people, as many as a populous city which disappears every year) are a drama that no one seems to want or to be able to face. In rural, less populous areas of the country, such as in the Montana of Wilkins' novel, the suicide rate is 25 percent higher than in the areas with at least one million people. Shocking numbers, meaningless, and which, when added to the deaths from alcohol abuse, reach unimaginable values of over 160,000 people who die every year "from desperation" and unfortunately the trend is constantly growing. The overshadowed and perhaps inexorably disappeared myth of a modern American society who seem unable to find the tools to put into practice what its founding fathers had decreed to be, in the Declaration of Independence of 1776, the inalienable rights for all men. Life, freedom and happiness.

by Paolo Tagliaferri 02/01/2021

Ultimi commenti

11.11 | 09:51

Sono trent'anni che mi occupo di sicurezza sul lavoro e credimi ne ho viste di tutti i colori! Un salutone super divulgatore !!!! Ciao Paolo

11.11 | 09:45

Ciao Paolo non sapevo che avessi oltre alla passione per la scrittura anche questo sito/blog. Tanti tanti complimenti hai una bella scrittura ed affronti un tema non facile. Ciao Marco

06.03 | 05:36

Ciao Paolo buongiorno! Si vede che sei la bella persona che conosco, aperta e attenta ai bisogni altrui. Mi riconosco in questo scritto ma c'è molto di più!

Condividi questa pagina